Behind “Behind The Mask”

Last month I made a trip to San Francisco to see some friends and take in the sights. Whenever I’m in the bay area I always make sure to stop by Amoeba, one of the world’s largest and greatest record stores, and buy as much as my suitcase allows (spoiler: I had to buy another suitcase). During this past visit, I scored some CDs and LPs by Ryuichi Sakamoto, the keyboardist of the legendary Japanese synth-pop band Yellow Magic Orchestra, and an accomplished solo artist whose work runs the gamut from silly pop music to Oscar-winning film scores.

One of his CDs that I picked up was Media Bahn Live, a concert album that chronicles his 1986 tour. One of the main reasons I bought it was because it features a live version of “Behind The Mask,” one of my favorite YMO tracks, and a song I first discovered on the American YMO compilation album X∞Multiplies. Here’s a live version by the group from 1983

In my opinion it’s a synthpop classic. It has everything I look for in the genre; a catchy melody, a dance-friendly beat, and deep, if somewhat obtuse, lyrics that convey a cold and robotic feeling.

So imagine my surprise when I popped Media Bahn Live into my computer and heard this version:

The melody remained (kind of) but nearly every other aspect of the song had been radically altered. This was no longer a synthpop track, this was a pop song, a funky, rock-influenced pop song at that.

And those new lyrics!? What the hell are they and where the hell did they come from?

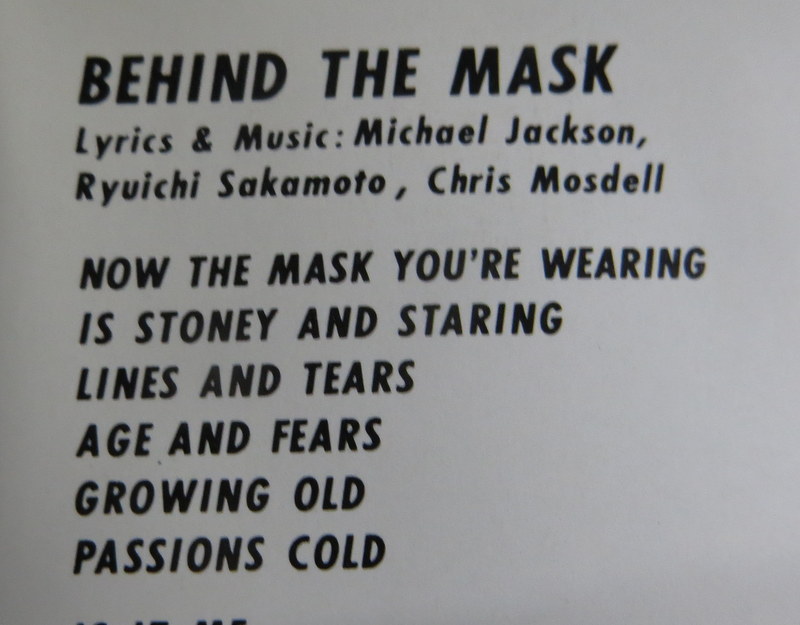

Curious, I checked the CD linear notes to see if any other songwriters got a hold of the song or contributed to it.

Wait, what?

As it turns out, “Behind The Mask” has a pretty crazy history.

As I mentioned earlier, “Behind The Mask” began as a Yellow Magic Orchestra song, but that name probably draws a blank to all of you, save for anyone from Japan or near-obsessive collectors of synth-pop who may be reading this.

Yellow Magic Orchestra formed in the late 1970s, consisting of Ryuichi Sakamoto on keyboards, Haruomi Hosono on bass/keyboards and Yukihiro Takahashi on drums and lead vocals. The group released their self-titled debut in 1978, and it’s widely considered to be one of the earliest examples of synthpop, pre-dating Western forerunners of the genre such as Gary Numan, and the poppier incarnation of The Human League. The album sold over 200,000 in Japan (that’s good) and it even cracked the Billboard Top 100 in the states, something that I believe was a first for a Japanese record.

The album sold so well that Japanese watch manufacturer Seiko contacted the group to make a commercial jingle for their new watch. They came up with a simple and catchy little tune.

Sound familiar?

Either YMO just gave Seiko a rough demo of a song they were already working on, or they knew they had something with it and decided to keep working on it. Regardless, a more polished version of the track eventually making its way to their sophomore album Solid State Survivor, and it was just one of many hits off of the album. The record was a massive success, one unlike Japanese artists had ever seen, eventually selling over one million copies in Japan and additional million copies overseas.

And one of those copies ended up in the hands of Quincy Jones while he was producing Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

While concrete evidence on this is rather sketchy, the most-commonly cited story I could find regarding this incident was that Jones was so impressed with the original song that he thought it could work as an American pop song. He passed it on to Michael, who then modified the melody and added his own lyrics, transforming the poppy-but-distant song about how Japanese culture can lead to isolation into a blistering rock/funk track about a love triangle. When the project was finished, both Jones and Michael thought they had a hit on their hands, but some sort of royalty dispute with YMO kept the song off of Thriller.

But whatever that dispute was, it didn’t keep other artists from performing or releasing it, and that’s exactly what happened.

That’s Greg Phillinganes. He started his career as a session musician, playing on albums by Stevie Wonder, Thelma Houston and Leo Sayer, among others, during the later half of the 1970s. He first worked with Michael Jackson in 1979, performing on his breakthrough solo album Off The Wall, and he worked with Michael again on Thriller, playing on most of the songs on the album, as well as several that didn’t make the cut – including “Behind The Mask.” So when Phillinganes went into the studio to record his sophomore album Pulse, he took “Behind The Mask” with him, keeping Jackson’s arrangement.

When comparing Phillinganes version to the YMO original, the most obvious difference is the Jackson-penned vocals, but there’s a lot more going on here than just a new vocal track. Most notably, the main melody of the song has been removed almost completely, and when it does show up, it’s buried pretty deep in the mix. Instead, the counter-melody has been pushed to the front, and since it’s much bouncier and upbeat, the song instantly becomes far more danceable.

The technology behind the track is different as well. The keyboards playing the melody on Phillinganes’ version are digital keyboards, as opposed to the analog synthesizers from the YMO original. That may not sound like a big deal, but it’s actually a key reason as to why the two versions sound so different from a production standpoint. There are a ton of differences between analog and digital keyboards, I don’t want to bore you with specifics, but the general gist is that the digital synths of the 80s were much better at creating big and powerful sounds with relative ease than their older analog counterparts were. It was so easy, in fact, that they pretty much became the dominant instrument in every genre during the mid-80s, showing up in everything from funk (Prince) to glam-rock (Van Halen) to blues-rock albums by washed up British guitarists.

After the relative failure of Pulse, Philliganes went back to being a session musician, eventually teaming up with Eric Clapton during the recording of his 1986 album August. Phillinganes didn’t just play keyboards on the album though, he also co-wrote several of the tracks, and apparently introduced Clapton to “Behind The Mask” as well. In the hands of Clapton, “Behind The Mask” was turned into a bonafide hit single in England, providing him with his first Top 20 single in his home country in years.

Okay, now I want you to think about that for a second. Because I think that shit is weird.

Eric Clapton, Mr. Slowhand himself, the king of British blues, not only covered a Japanese synth-pop song, but he’s covered a Japanese synth-pop song that started as a commercial jingle.

I think that’s weird. It’s weird, right?

Clapton did change the tune a bit when he got his hands on it too. The keyboards are pushed back a bit in the mix, with much more of an emphasis given to his guitar (obviously), as well as the drums (which were played by Phil Collins, by the way). Also, the vocoder vocals are removed entirely and replaced with a rather bland chorus of woman back-up singers.

The changes definitely make it the most pop-friendly of all the versions, and that, combined with it being a Clapton release, probably contributed to it being a top 20 hit in the UK, a feat that served as a stepping stone in Clapton’s comeback during the late-80s and early-90s. It’s safe to say that without Clapton’s cover of “Behind The Mask,” we might not have had “Tears In Heaven” or his career-defining Unplugged album.

Depending on how you feel about Clapton’s acoustic version of “Layla,” that might not be a good thing.

And if you think Clapton covering a Japanese pop song is weird (and like I’ve already went over, I think it’s pretty damn weird) then you should really check out some live performances from the era, when Clapton was routinely stopping by at various all-star benefit concerts.

Here’s Clapton playing the song with Mark King from Level 42 on bass, Jools Holland on keys, and possibly some of the members from Big Country in the backing band.

And then there’s this version, featuring Elton fucking John and Mark Knopfler from Dire Straits.

I mean, damn.

With Clapton’s version a hit in Europe, Sakamoto elected to take that version on the road with him in 1986, which in turn ended up on the live album I bought. Strangely enough, out of all the arrangements of the Jackson version, Sakamoto’s is the least electronic. It’s a guitar jam through and through. I didn’t expect that at all. When I first heard it, I couldn’t stand it. But after charting the song’s history, and it’s crazy transformation, I’ve found that I’ve been able to appreciate that version a lot more.

MJ’s take of “Behind The Mask” was finally released in 2010, on the posthumous Michael compilation, but strangely it actually doesn’t have a lot in common with the original YMO version. The counter-melody-turned melody from the Phillinganes’ version is gone completely, while the original melody only pops up from time to time. Perhaps the producers for Michael changed it to make it sound more “modern?” Regardless, it certainly is a great version of the song, and I can see why Phillinganes decided to cover it when he had the chance to. However, I actually think I like Clapton’s, and even Phillinganes’, versions more. Since they both keep that original melody in tact, they’re far more upbeat and powerful. There’s just more to them. Michael’s versions is little more than just his voice and a simple beat, which is much more of a modern sound (and why I think the producers of Michael fucked with the track), and just a little boring if you ask me.

It’s better than this though.

Sampling can sure be dangerous in the wrong hands.

Leave a Reply