YMO 101: The Solo Records

This is part four of my guide to Yellow Magic Orchestra.

Part 1: The Studio Albums

Part 2: The Live Albums

Part 3: The Compilations and Remix Records

Part 5: The Pre-Cursors and Side Projects

Part 6: The Protégés, Associates and Etc.

Before Yellow Magic Orchestra released their first album in 1979, all three members (Ryuichi Sakamoto, Yukihiro Takahashi and Haruomi Hosono) were already accomplished solo musicians to some degree. And their penchant for releasing music on their own continued on both during their time in YMO and after.

And I don’t mean they would occasionally release an album once or twice a decade. For a while, all of them were seemingly putting out music non-stop.

It’s probably fair to say that Takahashi, Sakamoto and Hosono are three of the most prolific musicians in the history of pop music, in Japan or otherwise. Combined, they have released literally hundreds of albums across nearly all genres of music imaginable. And that’s great. But it also makes jumping into their solo discographies an incredibly daunting task. Their output can just seem overwhelming at times.

So this part of the YMO guide is going to be a little different. Instead of going over every album the three put out, (which would be impossible for nearly anyone) I’m going to highlight what I think are the best and/or most accessible records of each member’s solo discography. Think of this is a jumping off point from where you can dive deeper if you so desire.

And I am only covering proper solo records here. Side-projects will be for another day!

Ryuichi Sakamoto

If there’s any member of YMO whose name is the least bit familiar to Western audiences, it’s probably Sakamoto, thanks to his rather prolific career as a film composer both in Japan and aboard. He won an Oscar for his work on The Last Emperor, and has continued to write film music throughout his career, contributing the films as diverse as Brian De Palma’s Snake Eyes, Oliver Stone’s wacked out mini-series Wild Palms, and most recently the nature snuff film The Revenent.

And all this time he’s also kept up his career as a solo musician, moving through wildly different genres with an impressive grace. However, it’s this prolific tendency for the eclectic that makes his discography the most daunting of the YMO members. If you pick up a Sakamoto album without first researching it, there’s no telling what you might get. It could be a beautiful collection of synthpop that puts YMO’s best work to shame. But it could also be a collection of jazz fusion, or a 60 minute uncompromising symphonic piece (although I actually like that one).

However, if you start at his proper solo debut, Thousand Knives, you’ll probably walk away happy. This is one of those albums that’s so breathtakingly original and ahead of its time that it’s difficult to write about, even some 37 years after it’s original release. It immediately signaled that he was a force to be reckoned with, thanks to its one-of-a-kind amalgamation of early electronic music, classical piano and even some touches of jazz, thanks largely to the amazing guitar work of Kazume Watanabe on both the title track and the finisher, the powerful “End Of Asia,” which YMO would later re-work for the X∞ Multiples album. Even more remarkable than the album’s innovations is the fact that it’s entirely listenable and enjoyable. A lot of groundbreaking electronic music is interesting from a historical or technical standpoint, but this is one of the only albums of its type that holds up as a collection of music, independent of its own innovations. It’s wholly original, but not at the cost of accessibility. A must own.

Two years later, Sakmoto released B-2 Unit, an more brutal and intense variation of the previous record. At its lightest, it’s off-kilter and bizarre. Mechanic tracks like “E-3A” have a robotic playfulness about them. But most of the album is dark and abrasive. The album opens with “Differencia” a two-minute blast of percussive noise, and closes with the sublimely ominous “The End Of Europe,” a dark looping nightmare that sounds straight out of a horror movie. It requires a bit more of an adventurous ear than Thousand Knives, but I still recommend it without hesitation.

The same goes for Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia, Sakamoto’s 1984 album that served as his first real attempt to break through into the international market, complete with alternate versions made for areas outside of Japan. That means that you might get a different tracklisting depending on which version you pick up, which can be kind of annoying. Although, whether you pick up the international version or the Japanese original, you’ll probably like what you find. Lots of good abstract synthpop here, definitely dialed down a bit from B-2 Unit. The US version even includes “Field Work,” Sakamoto’s collaboration with Thomas Dolby, so that’s a plus. Do keep an eye out for the 2015 deluxe edition however. While it is still lacking “Field Work,” it’s a two-disc set with nearly 30 tracks.

Next on the must-buy list is Futurist Bastard aka Futurista, from 1986. It’s my favorite Sakamoto solo release. At the same time though, I realize that it might not be for everyone, thanks to its somewhat slavish devotion to the idea of futurist music.

Let me explain: futurism is a complex term that has a lot of different meanings depending on the context in which it is used. When talking about music, futurism refers to the idea of replacing traditional musical instrumentation and sounds with those of machinery. Futurist music was first conceptualized in the early 1900s, with an early adherent in the school being one Luigi Russolo, who in 1913 wrote the manifesto The Art of Noises. Some 70 years later Trevor Horn must’ve stumbled upon a copy of that manifesto, got his first sampler, and went to town, with the end result being The Art of Noise and their breakout 1984 debut Whose Afraid Of The Art of Noise.

I assume that not soon after its release, Sakamoto got a hold of that record and though, “I can out futurist these motherfuckers.”

Sakamoto took futurism and ran with it on this record, sometimes combining futurist ideas with traditional pop songs, like he does with “Ballet Mecanique,” but often just going hogwild with them to craft entirely unique musical experiences. Jazz saxaphone mixed with industrial beats and samples from Blade Runner? Sure! Why not? How about ambient textures overlapped with actual passages from the first Futurist music manifesto? Sure! Opera mixed with techno beats? Go for it!

This record is not for everyone. But I probably listen to it more than any other of Sakmoto’s solo works. I think his best example of combining really out-there, avant-garde ideas with more traditional song structures and pop elements.

I guess the same would go for Discord. This album is INSANE. It’s a contemporary classical piece, with four tracks totaling 55 minutes. The standout is the briefest one, though, “Anger,” which is just five minutes of what could best be described as “orchestral noise rock.” Oh, and DJ Spooky is on here too, if you like your breakbeats with your orchestral music.

Even if you don’t like this record I still recommend picking up it’s remix companion piece, Discord Gutninja Remixes, which features reworks by artists like Coldcut and Amon Tobin. They add the beats and turn the pieces into actual songs at times, which probably makes it more accessible.

That’s about all the Sakmoto I can recommend without reservation. I realize that I left out a lot of his biggest releases, including Neo Geo, Beauty and Sweet Revenge, but I really do feel like all three of those albums are optional at best. They’re all Sakamoto trying to make pop songs for mass consumption, and not doing a particularly good job. Want good 80s pop music? Check out this guy.

Yukihiro Takahashi

Of the three members of YMO, Takahashi’s solo output is the easiest to dive into without the need for prior research. While he does occasionally make the odd foray into more avant-garde and experimental genres, the majority of Takahashi’s output is squarely in the realm of electronic pop music.

That isn’t to say that Takahashi’s sound hasn’t changed throughout the years, it definitely has. While his early work bears the markings of YMO’s trademark sound, throughout his career he as adapted to the times, striking into a more radio friendly sound for a bit, and then later on embracing a very modern glitch-pop sound.

A good jumping on point for Takahashi’s solo work is his second album, and the first after forming YMO, 1980’s Murdered By The Music. This is a fantastic record, and it might just be the best solo pop effort to date by any YMO member. It’s a damn near perfect record that really balances Takahashi’s penchant for radio-friendly pop tunes with a great ear for production and more interesting electronic instrumentation. Additionally, the entire album is in English, making it much easier for us foreign plebs to take in than most of his other work.

And when you look at when it came out, it’s really ahead of its time, much more advanced and layered than most of the synth-pop from that era. While most of the UK synthpop scene was focused on minimal, cold stuff like Gary Numan and The Human League, Takahashi was crafting wonderful pop tunes with real substance to them, like the title track, “School Of Thought,” and “Radioactivist.” The album even features a surprising (and surprisingly good) ska turn with the wonderful “Kid-Nap The Dreamer.” Great, great, great stuff

Neuromantic, Takahashi’s follow-up to Murdered By The Music would come just a year later. A lot of people consider this to be his best solo work, and while I obviously disagree, that has less to do with any shortcomings this record might have and more to do with just how great Murdered By The Music is. This is also a fantastic record, and probably one of the most “YMO-like” in Takahashi’s discography. “New (Red) Roses” and “Connection” could’ve easily been YMO tracks. The album also has one of Takahashi’s biggest solo hits, the melancholic “Drip Dry Eyes,” which he originally wrote for YMO associate Sandii & The Sunsetz the year prior.

In 1982, Takahashi released What, Me Worry? And it’s a fine record I suppose, but it’s a little middle-of-the-road for my tastes. Instead, I would recommend the album he put out the following year, Tomorrow’s Just Another Day. And I say that while admitting that it is a slightly uneven affair when compared to a lot of Takahashi’s 80s work. Some of it falls into a mid-tempo groove a bit too much, reminiscent of far too much forgettable middle-of-the-road synthpop that flooded the radio throughout the 80s (think Mister Mister or Cutting Crew).

But the highlights here are just too great not to recommend, most notably “My Bright Tomorrow,” which is one of Takahashi’s best songs. A brutally sad song that manages to tug at my heart every time I hear it, with it’s fast-paced electronic drum beat defying its cry for a rapidly vanishing hope for the future. If this song doesn’t speak to you I guess you should consider yourself lucky. Outside of that interstellar standout, there is some good to find here. “Kageru” is a pretty little tune, and “Are You Receiving Me?” stands out as the only fast-paced highlight on the record. Again, not his best work, but still worth the listen.

At this point, Takahashi’s solo output kind of takes a nosedive, really swerving too hard into the radio-friendly territory for my tastes, much like the weaker tracks on his previous two records. Wild & Moody, Once A Fool and Only When I Laugh are less records and more wallpaper. Inoffensive to a fault, boring as hell.

The only record from this time period that I can at all recommend without hesitation is Ego, which came out in 1988. Like a lot of his other lesser 80s work, it focuses a bit too much on the slower, more contemplative numbers, but when it does break through from that routine it sounds quite good. There is a lot to enjoy here, from the fun “Look Of Love” the the trippy as hell cover of The Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows.” Also worth a listen is his surprisingly good collaboration with Icehouse’s Iva Davies, the Bowie-eqsue “Dance Of Life.”

Throughout the remainder of the 80s and into the 90s, though, Takahashi’s work took an even bigger dip. I can’t recommend any these albums in the least. Just absolutely dreadful stuff that sounds like he was trying to hard to hit the mainstream. Not even going to bother naming them. They’re that bad.

But something changed in the mid-90s, starting with 1996’s A Sigh Of Ghost. It’s only six tracks, but at 34 minutes long I guess it qualifies as an album, and damn fine one at that. I don’t know what brought this album on, but it finally saw Takahashi break free of his seemingly unending desire for radio friendly technopop and really try something new.

And try he does. “Run After You” and the title track both invoke early glitch-pop experimentation of the era, and “A Smile” is funky dance tune with some 90s house elements. It has a couple slower numbers, but even they’re more on the creative side. “Tragedy/Comedy” combines acoustic guitar strumming with drum and bass beats to great effect, and the closer “Set Sail” may be a rather by-the-number pop tune, but it does feature a totally rad guitar solo, so that’s nice.

Takahashi would release another great record in the 90s, The Dearest Fool, which came out in 1998 and continues the glitch experimentation found on A Sigh Of Ghost. Unfortunately, he would take a break from solo recording for the next decade, and not return with another proper solo album until 2006 with Blue Moom Blue, followed in 2009 with Page By Page.

Fortunately, these two albums are FUCKING AMAZING. And really show Takahashi taking his glitch-pop influences into wonderful and beautiful new places. Seriously, Page By Page might be his second-best solo album after Murdered By The Music. It’s really remarkable and ripe for discovery. Check it.

If that was a lot, don’t worry, this next section will be much more brief.

Haruomi Hosono

Between the internationally acclaimed diversity of Sakamoto and the dependable pop music of Takahashi, I feel that Hosono’s unique solo contributions get somewhat lost in the mix. That’s a shame because, if anything, Hosono’s discography is the most impressive of all three for its radical diversity.

It certainly reaches the furthest back. While Sakamoto and Takahashi’s solo careers only slightly predate YMO, Hosono was recording music as early as the late-60s, working first as part of the hugely influential Japanese rock band Happy End, before moving onto a solo career that saw him embrace a very strange tropical/folk style that has little in common with the YMO sound we know him for today.

I have a hard time recommending any of these records outright. If you’re here looking for YMO-like releases, there’s just not much there for you. But if I had to recommend one, I guess I would suggest Paraiso, which came out in 1978 if for nothing else than its historical value. This album is credited to “Harry” Hosono and the Yellow Magic Band, which includes Yukihiro Takahashi and Ryuichi Sakamoto. It’s technically the first YMO record, and it’s a lot of fun. Good for parties.

During YMO’s prime, Hosono only put out one solo record, Philharmony, which came out in 1982. And it’s the first release by him that I can hardily recommend to YMO fans. Although, be warned; this record is really weird. It has much more in common with Sakamoto’s experimental solo material than anything that YMO put out as a group. Some of it has an Eno ambient quality to it, while other tracks are derivative of early-80s synthpop in the best way possible. Human League, Gary Numan and Ultravox are all over this album, and that’s a good thing.

Immediately after YMO called it quits in 1984, Hosono released S-F-X. High quality synthpop here, starting with the amazing “Body Snatchers” and moving on the Art Of Noise-inspired title track. Most CD re-issues also include tracks from an EP that Hosono put out around the same time, all of which are bizarre instrumental snippets that should appeal to you if you liked Philharmony.

The same year saw the release of Video Game Music, and while Hosono is credited as the artist on that one, I tend to think that’s wildly misleading. This is a collection of early video game music that Hosono produced and occasionally remixed. That’s it. So, if hear noises from Xevious and Mappy are your thing (they’re certainly mine) then snag this one. Otherwise skip it.

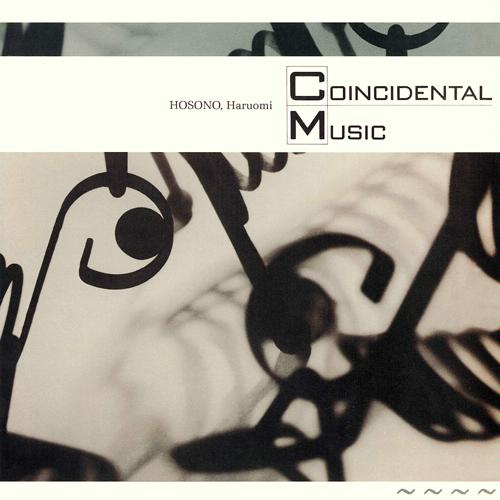

After 1984, Hosono would take a hard swing towards ambient. He released four albums in 1985, Paradise View, Coincidental Music, The Endless Talking and Mercuic Dance. They’re all ambient, again very much in the Brian Eno sense. Quiet, relaxing records for quiet relaxing times. Ditto for Medicine Compilation, which came out in 1993. It does mix things up a bit with a few upbeat tracks, but for the most part it’s another instrumental ambient record. I love this stuff, but I get it’s not everyone’s cup of tea.

He would follow that one up with Interpieces Organization in 1996, which is credited to him and Bill Laswell of Material fame. It’s probably my favorite of his post S-F-X releases, combining his obvious love for ambient with other areas of electronic music, such as drum and bass and IDM. Very experimental, very out there, but very much worth your time.

From there, Hosono would take a 10 year break from solo recording and return with some soundtracks, and acoustic albums, seemingly going full circle back to where he started. These may be great records, but they’re not my thing in the slightest, so you’re on your own if you want to check them out.

I hope that helps someone out there delve into the labyrinthine worlds that are the YMO members’ solo discographies. If you have any recommendations you’d like to share, please do in the comments. Just don’t come at me with “your opinion is wrong” comments, they’ll be deleted.

Coming soon (and I mean it this time) will be part five, which will take a look at the various YMO side-projects. Seriously, it shouldn’t take me that long, they don’t have that many when compared to their solo work.

Leave a Reply